Elsa Cabrera, executive director Centro de Conservación Cetacea

The most recent plenary meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC69 held from September 23 to 27 in Lima, Peru, provided a new interpretation of the age-old proverb “troubled waters, fishermen’s gain.” The waters through which the IWC’s more than 80 member nations needed to navigate in order to approve the proposal for the establishment of the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary appeared markedly clearer and more calm since its initial introduction in 1998.

During the first day of the sessions, a considerable number of countries were notably absent—several of which alredy had voting rights—leading to a reconfiguration of the agenda that allowed for decisions regarding amendments to the Convention’s schedule, including the sanctuary, to be addressed on the fourth day of this international gathering. This strategic reorganization aimed to ensure there would be adequate time to achieve a representative quorum and secure the necessary votes for the adoption or rejection of the various initiatives on the table.

As every amendment proposal, the proposal for the creation of the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary, requires at least 75% of the votes from IWC member countries for approval. This threshold was reached in both 2011 and 2022, yet the proposal could not be adopted due to persistent blockages generated by nations aligned with Japan’s whaling policy, who either left the conference room or simply abstained from entering during the voting process — in an attempt to “break” the quorum for decision-making.

Consequently, preparations for 2024 not only focused on ensuring the necessary votes but also on guaranteeing that the presence of conservation-oriented nations in the meeting would be enough to secure an independent quorum to proceed with the voting procedure, even in the face of potential new endeavors by Japan’s allied nations to obstruct this democratic process.

What no one anticipated were the decisions made by the Chair during the IWC69, represented by Australia, which extended voting rights to countries that had not fully settled their membership dues. Up until the meeting in Lima, the regulations governing this international body have been clear and stringent concerning voting rights. According to the current IWC regulations, each country is entitled to participate in decision-making through its vote only if it has fully paid its annual membership fees. Even the slightest outstanding amount, such as interest accrued from a late payment, can previously stripped countries of this right.

In the case of Chile, which had arrears totaling two years’ worth of unpaid dues, civic organizations spearheaded by the Cetacean Conservation Center, Ecoceanos, and the Latin American Observatory of Environmental Conflicts (OLCA) initiated a successful campaign. With crucial public support, they managed to exert enough pressure on the relevant authorities to settle the outstanding debt just days before the assembly begun, allowing Chile to participate fully in this significant international gathering.

Nevertheless, on the first day of the plenary sessions in Lima, the Chair announced its decision to extend voting rights to three contracting governments that still maintained smaller debts, if they signed a payment plan. It further ruled that countries providing evidence of being in the process of paying their membership dues could also restore their voting rights. While these decisions, known as Chair’s rulings, can technically be challenged by any member nation of the IWC, none did so. The silence further twisted the regulations, ultimately compromising the creation of the Southern Atlantic Whale Sanctuary.

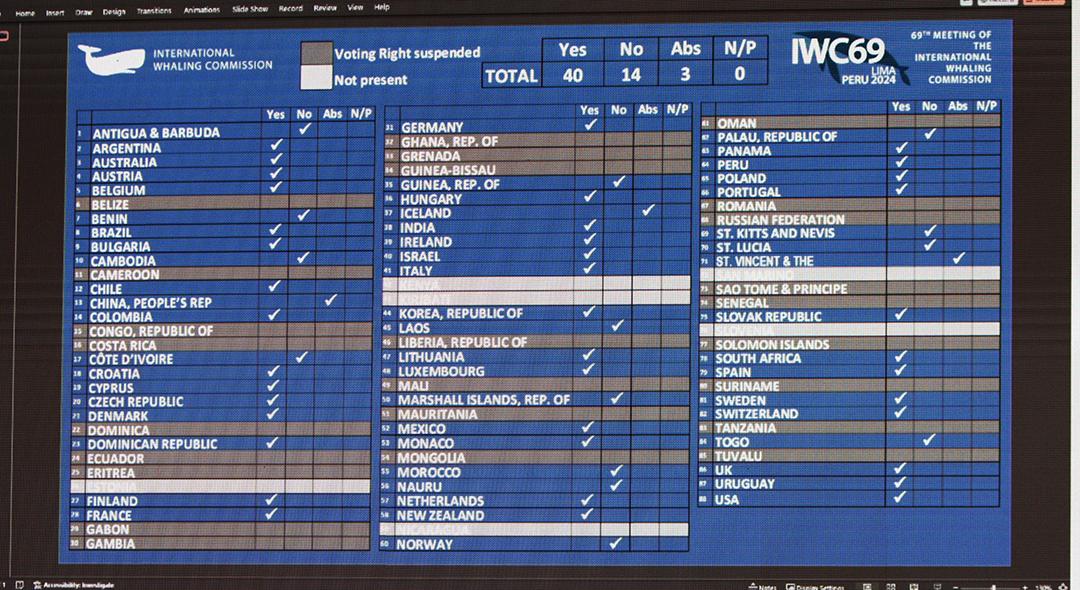

Thus, under these new and temporary rules, applicable exclusively to the plenary assembly in Peru, we arrived at Thursday, September 26—the eagerly awaited day for the potential establishment of the Southern Atlantic Whale Sanctuary. Before the vote, the IWC secretariat announced that nine countries had restored their voting rights through (1) full payment of their membership dues, (2) agreeing to a payment plan, or (3) providing evidence that payment was in progress. Notably, only two countries—Antigua and Barbuda (aligned with Japan’s whaling policy) and Panama (a conservation-minded nation)—met the requirements dictated under the current IWC regulations by fully settling their debts.

The remaining seven countries restored their voting rights via the submission of supporting documentation indicative of payment in process (Benin, India, Morocco, and Saint Lucia) or by signing payment plans (Ivory Coast, Guinea, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines). However, strictly speaking, at the time of the vote, these nations probably still held outstanding debts with this international body.

Among these last two groups of countries, only India belongs to the conservation-minded bloc that supports the sanctuary; the other six are aligned with Japan’s harpoon diplomacy within the IWC and are fundamentally opposed to, or have boycotted, its approval whenever circumstances favored such an outcome.

Under these prevailing circumstances, the proposal to create the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary garnered 74.07% of the necessary votes for approval. By a narrow margin of less than 1%, the long-held aspirations of many countries in our region to establish the sanctuary were, once again, deferred.

Had the IWC’s existing regulations concerning membership dues and voting rights been rigorously upheld, the South Atlantic Whale Sanctuary would have been approved with a historic support of 81% of the votes of the Commission.

Thus, amidst unexpected rulings and the Commission’s silence on these temporary changes to its regulations, we return to the proverb that initiated this discussion. In the aftermath of this meeting, it now stands poised to be rewritten in history as “twisted rules, whalers gain.”

Image table of voting: (c)IISD