After finishing the opening day without major news, on Tuesday the International Whaling Commission (IWC) continued its second day of plenary sessions addressing proposals that show that certain circumstances and the global political reality could end up damaging the conservation of cetaceans.

One of the first topics was the possible creation of a management committee that would be in charge of addressing whaling issues. The problem with this committee is that whales are globally protected by a moratorium. The intention behind its creation is not difficult to decode if we take into account that in 2018 Japan announced its was leaving the IWC after the commission rejected a proposal aimed at creating a committee with similar characteristics. That is why it is striking that countries that call themselves conservationists and ‘committed to the moratorium’, such as the European Union, the United States and Australia, expressed their support for its establishment. Others, such as Costa Rica, Chile, Argentina and the Dominican Republic expressed concern and opposition to its creation, so the issue was postponed until next Thursday in order to continue the negotiation process.

In the opposite direction and completely in line with continuous efforts from various international environmental bodies, Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay presented the proposal to create the South Atlantic whale sanctuary. Among other things, it would protect cetaceans from the increasing whaling pressure within the IWC, promote conservation in a large marine area and foster scientific collaboration in the region.

The proposal, which has been tabled for more than 20 years, has failed to achieve 75% support from the Commission, which is curious because only three countries in the world maintain commercial whaling operations (Norway, Iceland and Japan). However, the situation begins to make sense when we consider that the Japanese government’s so-called harpoon diplomacy (as member, and now, former member of the IWC), has been characterized by keeping an active group of countries within the Commission to support its’s whaling policies in exchange for fisheries aid. Blocking the creation of the sanctuary has always been part of their agenda. But after the COVID-19 pandemic, this situation could change. The nonappearance of several of these countries at the present meeting could become an opportunity for its possible approval next Thursday. However, it is essential to remember that every vote is vital for the creation of the sanctuary, so the absence of important conservationist countries such as Colombia and Monaco is, at the very least, alarming and very inconvenient.

Continuing with a 21st century agenda, the European Union presented a proposed resolution on marine plastic pollution. Its adoption would allow the IWC, among others, to become involved in the work being conducted by the United Nations to create a Global Agreement Against Plastic Pollution. Since this type of pollution is one of the greatest threats to cetaceans in the world, it is inexplicable that Norway, one of the countries in charge of leading the process of creating this international agreement, expressed its rejection in its best Japanese style, arguing that ‘the IWC only has competence for the regulation of whaling´. Fortunately, it was the only country with this position so it is expected to be adopted on Thursday.

The surprise came when Gana, on behalf of a group of African countries known as COMHAFAT/ATLAFCO presented a proposed resolution that seeks to use whales for food security. Considering that none of the proponent countries consumes whale products, it looks like this proposal represents the interests of another nation. And although similar proposals were already dismissed in 2016 and 2018, this time some countries, again conservationists, opened the door for deliberation next Thursday, by affirming their commitment to continue working on the text to reach an agreement.

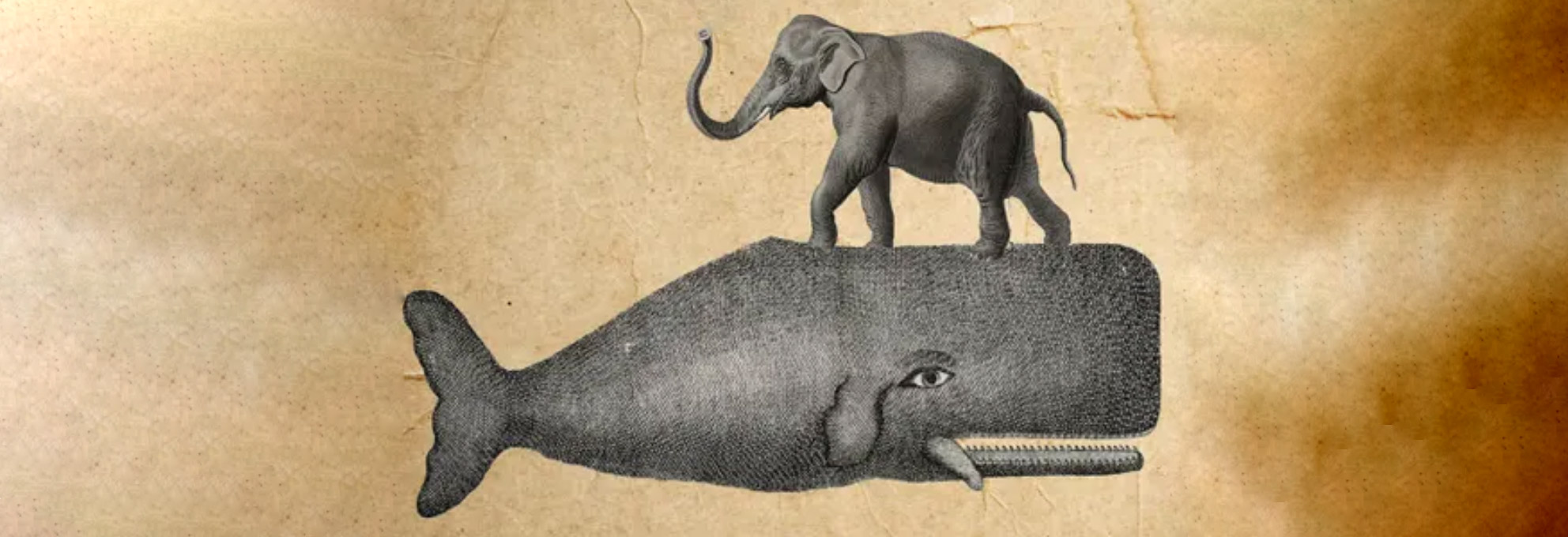

And at the end of the day, the most fervent representative of Japan’s whaling interests at the IWC, Antigua and Barbuda, took more than 20 minutes to present a proposed resolution aimed at lifting the moratorium. His arguments were mainly aimed at questioning the legitimacy of this international body. For Antigua and Barbuda, the IWC is a static body that should orient its work to the principles and vision of its founding members. The problem is that those principles and vision were adopted 75 years ago, and the world has changed since then. For Antigua and Barbuda, the IWC’s inability to lift the moratorium and dedicate its efforts to killing whales as it did in 1947 is ‘an elephant in the room’ that threatens to discredit its work and could end up destroying this international organization.

But a quick review of the issues of the day suggests that the elephant in the room is something else. It appears that this elephant continues to manipulate the IWC’s agenda through harpoon diplomacy and takes advantage of the global political reorganization to advance its interests through former rivals in the Commission.

On Thursday we will see where the whales and the future of the IWC stand amid this complex landscape.

By Elsa Cabrera, director of Cetacea Conservation Center and accredited observer to the IWC since 2001.